INVESTING IN PLANETARY HEALTH AND HUMAN SURVIVAL:

Does it meet the test of the prudent person?

Keynote Address to the Social Investment Forum, Thursday

October 5, 2000 – Snow Mass Resort, Aspen, CO

By David C. Korten

It’s always a thrill to speak to a group with such energy and commitment that is making a real difference in the world. It is a special privilege to be sponsored and introduced by Amy Domini, who has made such an extraordinary contribution to the socially responsible investment community. We have a lot of big issues to cover today, so let’s get right to it.

As we heard last night from Emily Matthews of the World Resources Institute, we live at a moment of profound choice. It is a frightening moment because if we continue on the present course of what she described as the Market World, we end up not with its promise of limitless wealth, but rather in Fortress World, a place where no sane person would want to live. In the large sense our choice is thus between Fortress world or Transformed world.

For all the risks of this historical moment, the fact of the choice before us makes this an unusually exciting time to be alive, because we face both the opportunity and the necessity to take the step to a new level of human consciousness and function. The creative challenge is enormous when you consider that our continued survival as a species requires that we rethink and recreate ourselves and our institutions to create a world that works for the whole of life. It presents a creative challenge without precedent in human history. When before has the whole of humanity had the opportunity to join together to make a collective choice as to what we wish to become?

If you are interested in learning more about the forces building behind the change of course toward Transformed World, I encourage you to subscribe to YES! A Journal of Positive Futures, which is published by and for people working for a Transformed World. It is a wonderful source of information and inspiration on the possibilities and the momentum building behind their realization.

As you will recall from last night, Fortress World is the outcome of three powerful current trends: the ongoing destruction of the life support systems of the planet, which is reducing the ability of the planet to respond to the demands of a growing and increasingly affluent population; increasing extremes between rich and poor; and a disintegrating social fabric. As the trends deepen we may expect that the wealthy, who are consolidating their control of what’s left of the resource base, will continue the current trend toward setting themselves apart in increasingly fortified communities in the midst of a sea of poverty and violence. How long they will be able to maintain their protected strongholds is anyone’s guess. It is a nightmare scenario. And it is a direct outcome of the policies and dynamics of what WRI calls the Market World.

I would differ with WRI only in noting that what they call the Market World is more accurately named the Capitalist World. As I will elaborate later, a capitalist system, which is about concentrating control over productive assets in the hands of the few to their exclusive benefit, is very different from a market system, which is about people creating their means of livelihood through the production and exchange of goods and services. The difference is key to our thinking about the choice ahead and I’ll return to it later.

The WRI presentation makes an excellent backdrop for our discussion this morning on the theme of governance. How have we organized ourselves as a global society to make the choices that will determine our collective future and why does this lead us to make such bad decisions? What institutions determine who makes the decisions? By what criteria? And to whose benefit?

That brings us to the business sector, which as WRI notes, is now human society’s most powerful institutional sector–the sector that is in fact currently setting humanity’s priorities. More specifically the controlling power resides with global finance and corporations–particularly the global financial market. This market holds governments hostage to its interests on threat of raiding their currency if they promote policies that financial speculators consider unfriendly. When that happens economies crash and government’s fall. The financial market holds corporations hostage by trashing the stocks of companies that are lagging in shareholder return, staging a buy-out, or simply firing and replacing top management.

Let me just do a check here with a quick show of hands. How many of you agree with the statement that business is the most powerful institutional sector and that more specifically financial markets and corporations are the dominant institutions setting human priorities. [Most hands were raised.]

And how many feel this is a good idea–meaning that you feel comfortable leaving it to global financial markets and corporations to decide for us whether or not we will change direction from the path to a Fortress World toward the path to a Transformed World? [No hands were raised.] So it seems we are all on the same page with regard to the crux of our problem.

Let’s begin with some graphs that give a useful overview of what’s happening. This graph represents per capita figures for the United States in 1992 dollars. We see in this graph the strong growth in stock market capitalization and gross domestic product (GDP). The politicians and pundits of the corporate press point to these trends, particularly the rapidly rising stock market and tell us the economy is doing well and we’ve never been so prosperous–though it seems strange that if we are so prosperous we cannot afford to provide our children with good schools and provide everyone with adequate health care.

Compiled by Mark Anielski, 2000

We hear less about the economy’s most impressive growth curve, however, the growth in debt. We have about $80,000 of it for every man, woman, and child in the United States. It seems our economy runs on debt, which is a serious issue, because debt narrows our choices. If any of you have had to pay off an education loan, you know very well what this means by how it limited your career choices to those that would pay a sufficient salary to pay off your debt while making a living. This debt is a part of the governance picture, because it has a great influence on the behavior of people, governments, and businesses. Our whole society has fallen captive to money lenders.

Its also significant that the largest single debtor in this picture is the financial sector – $7.7 trillion. This is the sector whose only product is money. Its debt is called leverage. So we see financial institutions frantically borrowing money to make money on money for people who have money–and the goal is to do it without ever bearing the inconvenience of becoming involved in the actual production or exchange of real [non-financial] goods and services. Much of this money is used to fuel financial speculation–as with the case of the now infamous hedge-fund Long-Term Capital Management, which leveraged its currency speculation operations on a ratio of 25 to one and put the entire U.S. financial system at risk. This borrowing is also used to inflate the prices of stocks far beyond what is supported by earnings–in short to create financial bubbles.

The second largest debt is household debt, which is now about 98 percent of disposable household income in the United States. This reflects the growing gap between household expectations and income. It also means that many households are turning over to the banking system much of what otherwise would be discretionary income or savings. Its called debt slavery.

There is also America’s foreign debt, which is the collective gap between our consumption and our own production. The overall U.S. current account deficit in 1999 was $221 billion, up from $79 billion in 1990. It’s another form of consumer debt that reflects imbalance of our consumption in relation to the rest of the world.

Then there is the U.S. Genuine Progress Indicator. Some thoughtful economists have noted that GDP is simply the gross market value of all the goods and services bought and sold in the market place. An increasing share of this total represents goods and services that are either harmful or are a response to harms that are in many instances a consequence of economic growth. For example selling guns and cigarettes to children increases GDP. Getting divorced is good for GDP as you have to hire a lawyer. Someone has to buy or rent a new home and outfit it. Falling levels of trust result in the buying of home security systems and the hiring of more security guards and police. When we cut down forests, the sales price of the timber counts as growth, but there is no deduction for the loss of trees and ecosystem services.

Economists at Redefining Progress, a nonprofit think tank in San Francisco, have adjusted GDP to create a Genuine Progress Indicator that more accurately reflects our actual economic well-being. The index improved in the United States on a per capita basis until the late 60s or early 70s, when the trend reversed and began falling. This means that though GDP per capita is growing, our actual well being is declining.

The line that starts below zero and is falling ever deeper into negative territory is a measure of the costs of the environmental degradation we heard about last night. This is a proxy for the loss of environmental services, arguably the foundation of all real wealth.

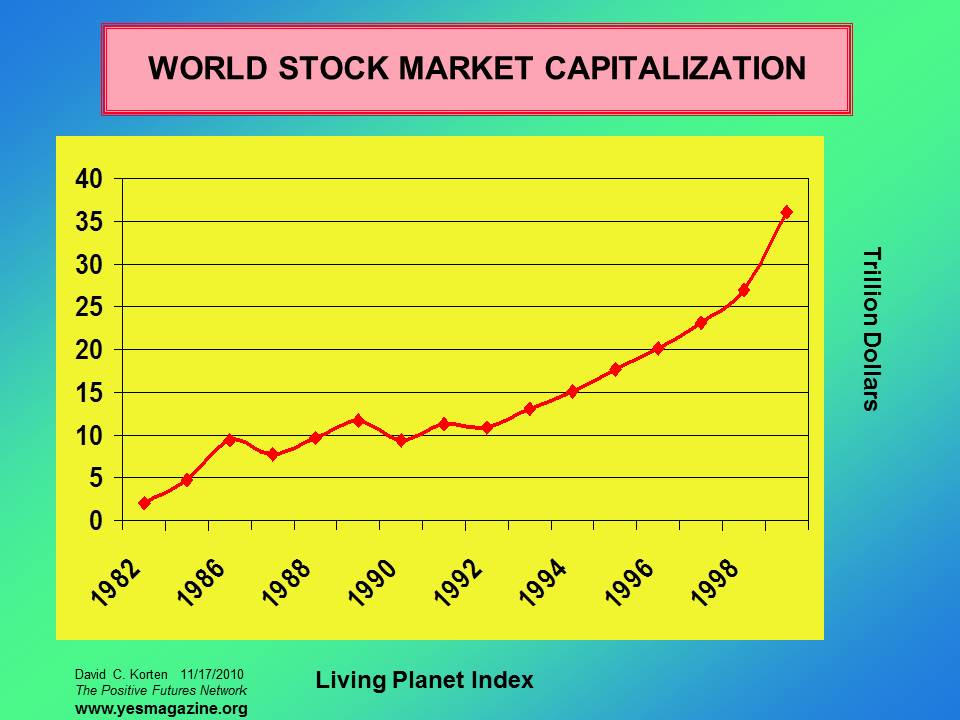

Now let’s look at a couple of graphs that show global trends. This graph shows the growth of total world stock market capitalization from $2 trillion 1982 to $28 trillion 1999. Global capitalists, those of us who live from returns to money, are doing quite well. Meanwhile, nearly half the world’s population lives on less than $2 a day and 1.3 billion people live on less than a $1 a day.

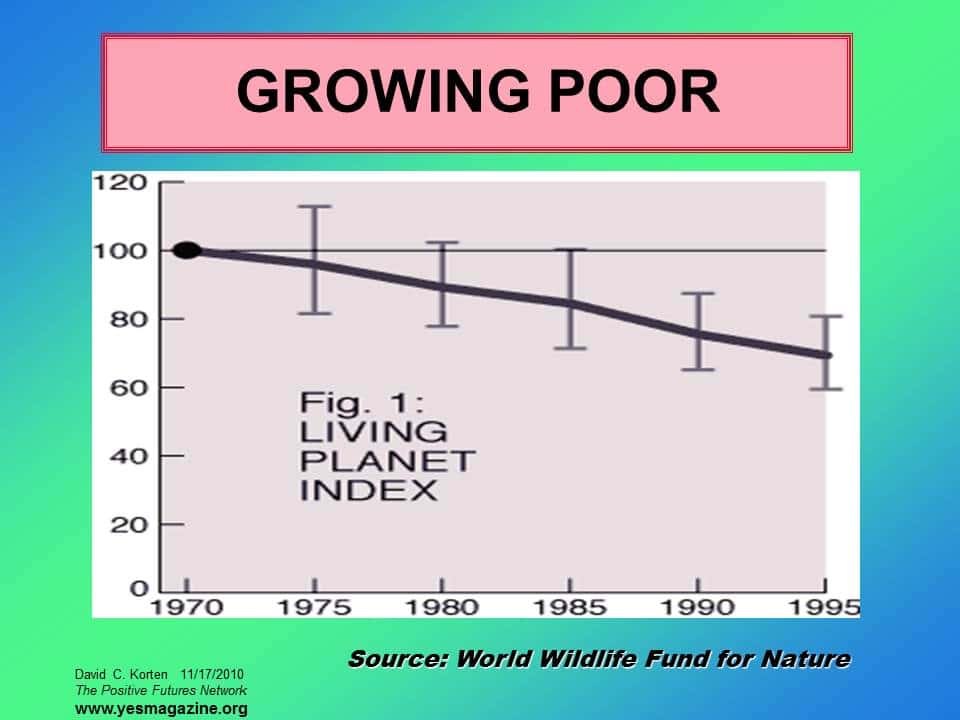

This graph presents the Living Planet Index compiled by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature to show the rate at which we are depleting the regenerative capacities, the natural wealth production, of the Earth’s forest, freshwater, and marine environments–all the things Emily Matthews was documenting. The index fell by approximately 30 per cent between 1970 and 1995. That means we have depleted 30 percent of the world’s natural regenerative wealth in one generation. Forests are shrinking, water tables are falling, soils are eroding, wetlands are disappearing, fisheries are collapsing, range lands are deteriorating, rivers are running dry, temperatures are rising, coral reefs are dying, plant and animal species are disappearing, and the climate is being more unstable. Entranced by the stock market’s illusions of wealth creation we scarcely seem to notice that we are destroying the foundations of real wealth and our very existence.

To fully get the picture on what we are doing to ourselves it is important to get really clear in our minds that money is not wealth. It is only a claim on wealth. You see money is only a number that has value only because by social convention we agree to accept it in exchange for things of real value like our labor, food, land, ideas, shelter, transportation, and energy. The financial system doesn’t create any of these. It only creates and allocates money, which in turn determines who gets the real wealth. The institutions of finance are the modern society’s ultimate control system. They control access to all the things we need to live and prosper, which is part of what gives them such power.

Here we see the overview. Financial assets and the claims of the rich against real wealth of the world are growing fast. These claims are becoming ever more concentrated in the hands of a fortunate few. The wealthiest 10 percent of Americans now own almost 90 percent of all business equity, 88.5 percent of bonds, and 89.3 percent of stocks. From 1973 to 1998 productivity in the United States increased by 33 percent. Though wages have been rising the past couple of years, the median wage is still slightly below 1973. It’s a direct result of a combination of the Federal Reserve Bank policy of raising interest rates to cool the economy if unemployment starts to fall, the imposition of barriers by government and management to suppress labor organizing, and the movement of jobs abroad by large corporations. All are aimed at keeping wages low and stock prices high.

Rising stock prices increase the financial assets of the rich far faster than the economy is increasing the production of the goods and services (GDP) that money might buy. Meantime, the pool of natural capital, the ultimate foundation of the productive system is in decline. So overall we have a growing population divided between the few whose financial wealth is growing rapidly and the many who live on static incomes, competing for a limited and declining base of real wealth. This is the real meaning of inequality.

We hear about the dematerialized information economy that creates no environmental burden. It may or may not be true that the production of the financial wealth of the dot-com millionaires didn’t create much environmental burden, but take a look at their consumption habits, which tend toward SUVs, trophy homes, private jets, and exotic vacations in remote parts of the world, and then tell me again about the dematerialized information economy.

This is a part of the story of the economic system leading us toward fortress world. Which takes us back to the question of why are we in this mess? Where does the institutional power lie. Who’s making the decisions? By what criteria? And to whose benefit? By now we should be pretty clear about where the institutional power lies. Its in the financial system. And with who is making the decisions. In part it’s us, those of us in this room, assuming that most of us here are of the capitalist class–meaning we live primarily from returns to money. So what about the criteria.

Most of the money floating around amongst financial institutions and instruments is now aggregated into investment pools under the care of professional money managers, most of whom are in fact or perception bound by the rule of the prudent person. By the strange logic of finance, the prudent person is one who takes care NOT to sacrifice financial return for some greater social or environmental good. Since money is nothing but a number, while society and nature are essential foundations of our existence and well-being, and the practice of prudence so defined is leading us toward collective suicide, we must conclude that by this definition the prudent person is also a psychotic sociopath.

The fact that those who are deciding the fate of human society feel bound by law to behave in their professional capacities like sociopaths is one key to understanding why humanity is in such deep trouble. The socially screened fund with its legal caveat that it is not limited by strictly financial considerations is a step in the right direction, but even with their spectacular growth, such funds remain the exception.

It is perhaps worth noting here that according to a recent Business Week poll, 95% of Americans believe corporations should sometimes sacrifice some profits to make things better for their workers and communities. It seems a remarkably sensible idea. If society is ever going to work for everyone, then surely the world’s most powerful institutions must be willing to sacrifice some shareholder return for a greater good. The poll suggests that the vast majority of Americans are a good deal more sane than the so called prudent person. This may say something about the future potential for socially screened investment funds.

Of course there are those who argue that there is no conflict between profit and responsibility, because doing the right thing is in fact more profitable than doing harm. Indeed, much of the legitimacy of the existing economic system rests on the theoretical premise that the market is governed by a wondrous invisible hand that magically turns the blind pursuit of individual financial gain into public benefit. We know it must be so because Adam Smith made a passing reference to the invisible hand in his book The Wealth of Nations. The sentence containing that reference is arguably the most influential sentence ever written by any human being, as we have since come to accept the benevolence of the market’s invisible hand as an article of unquestioned faith and as a result given over the power to determine humanity’s priorities to institutions that value only money, pursue its replication as their defining purpose, and cannot see beyond next quarter’s financial report.

There are indeed many cases in which environmentally responsible actions do increase profits. Hunter Lovins will surely share examples of such happy coincidence tomorrow afternoon. We have no reason to believe, however, that this is the general case. Those who design executive pay packages don’t seem to think so. Otherwise the CEOs of major U.S. corporations surely would not be receiving an average of $12.4 million in annual compensation, mostly in stock options. Recall that these extravagant pay packages are generally justified on the ground that they are necessary to assure that the CEO maintains a clear focus on shareholder return–which I believe is a code phrase for not getting side tracked by possible concern for the well being of workers, the environment, or the community. This suggests that CEOs must in fact be the most ethical people in the world, because one must pay them so much to get them to neglect the interests of people and nature.

Remember the story about King Midas? When granted a wish, he asked that all he touch turn to gold. However, when his touch turned his food, his drink, and even his beloved daughter to gold he realized his presumed blessing was a curse. Trading life for money has always been a bad bargain–but that is exactly what the global corporation is programmed to do in response to the demands of global finance.

- It turns the natural living capital of the earth into money when it strip-mine forests, fisheries and mineral deposits, produces toxic chemicals and dumps hazardous wastes.

- It turns human capital into money when it employs workers under substandard working conditions that leave them physically handicapped.

- It turns the social capital of society into money when it pays substandard wages that destroy workers emotionally, leading to family and community breakdown and violence.

- It turns the living trust of our public institutions into money when it bribes politicians with campaign contributions to convert the taxes of working people into inflated corporate profits through public subsidies, bailouts and tax exemptions.

It is a fundamental premise of market theory that for markets to allocate efficiently, full costs must be absorbed by the seller and passed on in the selling price to the product’s buyer. Next to obeying the law, the full internalization of costs is arguably the most fundamental social responsibility of any business. Indeed, if all businesses were fully internalizing their costs, we surely would not be experiencing our present crisis. Unfortunately there is a strong case to be made that corporate profits depend largely on their ability to pass enormous costs onto the public.

Paul Hawken a former corporate CEO and founder of The Natural Step USA, has compiled data demonstrating that corporations in the United States now receive more in direct public subsidies than they pay in total taxes. That’s only a small part of the story as it doesn’t include the costs to society of unsafe products, practices, and workplaces or from outright corporate crime. In the United States we have over billing by medicaid insurance contractors of $23 billion. Over billing by defense contractors of $26 billion. Fifty-four billion dollars a year in health costs from cigarette smoking. One hundred thirty-six billion dollars for the consequences of unsafe vehicles. Two hundred seventy five billion dollars for deaths from work place cancer. Pretty soon it starts adding up to some real money.

Some of you may be familiar with the book by Ralph Estes, Tyranny of the Bottom Line: Why Corporations Make Good People Do Bad Things. In that book, Professor Estes compiled an inventory of studies estimating the costs that corporations externalize onto the public in the United States each year in the form of such things as defective or dangerous products, environmental damage, and workplace hazards. He came up with a total of $2.7 trillion a year in 1994 dollars. That’s is roughly five times 1994 corporate profits in the United States and 37 percent of 1994 U.S. GDP. These are sobering statistics, because they suggest that if corporations did nothing more than recognize their responsibility to fully internalize their own costs, not only would their profits disappear, they would as well go out of business.

Environmental business journalist Carl Frankel reports in his book, In Earth’s Company on his effort to identify individuals working within large U.S. and Canadian corporations who were true environmental champions. He found three. All had been fired before he completed the book.

Paul Hawken spent years seeking to educate corporate executives to their environmental responsibilities through the Natural Step program. He reports “The number who are truly receptive can be counted on one hand. I am constantly confronted with skepticism and resistance.”

Robert Monks, a stanch Republican conservative, political appointee in the Reagan administration, successful investment fund manager, and leading authority on corporate governance, observes that, “Corporations are not people; they have no conscience. Although corporate acts are carried out by individuals, even individuals with high moral standards often find themselves caught up in a corporate action that is beyond their control–or even, in some cases, their knowledge.”

Monks goes on to note that for most corporations even decisions as to whether to obey the law are primarily a matter of financial costs and benefits, “The corporation in effect asks whether the costs of disobedience–discounted by the probability of being discovered, prosecuted, and fined (there is almost no risk of jail)–equal the costs of compliance.”

Given the size and number of the corporate crimes regularly reported in The Wall Street Journal it appears that many corporations find breaking the law to be a highly profitable business practice. Indeed, you are far less likely to go to jail for committing corporate crime than for participating in a street protest calling for corporate accountability.

So we have a problem and it is deeply imbedded in our economic institutions and their relationships to government and to civil society. If we are going to change course away from Fortress World to Transformed World, we will need to rethink and recreate out economic structures in ways that restore democracy, an ethical culture, and the conditions necessary for efficient market function–which among other things will require that we eliminate the institutional form of the publicly traded, limited liability company as we know it. That may seem like a tall order, but getting rid of kings wasn’t so easy either.

This brings us face to face with what for the socially responsible investment community tends to be a sensitive issue. The spectacular growth of socially responsible investment is built on the premise that socially screened funds can and do achieve greater financial returns than unscreened funds. This is sometimes turned into the claim that socially responsible investing is more profitable than the other kind, which presumes that the invisible hand is indeed real and the market rewards the responsible and ultimately punishes the irresponsible. It raises a very serious question.

I had my first serious awakening to the reality of social screens some years ago when I invested in the Citizens Index Fund. It is of course an exceptional fund that has produced some spectacular returns. At the time I had been talking to a colleague from India who was telling me about the frightfully irresponsible behavior of Enron in his country. By his account Enron was paying millions of dollars in bribes to get approval for an overpriced energy project that would cause massive social and environmental damage. While going down the list of firms in which Citizen Index Fund was investing at the time, one name in particular caught my eye: Enron. Then I saw Coca Cola, a firm that spends massively on advertising to get kids to spend their money on high priced sugar water. Etc. Etc.

The growth of socially screened funds is important, because it sends an important message that many investors do care. It is also an important consciousness raising experience for the investors who participate. But so long as we expect socially screened funds to rival unscreened funds in producing returns of 20, 30, 40, or 50 percent or more, we ignore some troubling questions. For example, if a socially screened fund is producing such spectacular returns, how responsible can it be? What is a fair and proper return to a passive investor in a just and sustainable world?

Are there any truly responsible publicly traded, limited liability corporations, by which I mean firms that make truly beneficial products, respond to customer demand without trying to create artificial wants, treat their workers well, never discharge harmful wastes, accept no government handouts or special tax breaks, and do not support or engage in any lobbying activities that seek special advantages from government or that seek to block or defeat beneficial social and environmental reforms?

As we noted earlier, money is not wealth. It is an accounting chit that gives the holder a claim over the real wealth of society. The allocation of money determines the allocation of societies resources. How much of the benefit of economic production will go to shareholders? How much to working people? How much will be directed to government to be used to provide social and physical infrastructure, public services, and a safety net for those otherwise unable to support themselves.

When shareholders enjoy 50 percent returns while working people find their wages stagnant or falling and schools are crumbling and millions are without health care because corporations are paying less than their share of taxes, it is an indication that the system’s priorities are terribly out of whack. We might ask whether in a just and sustainable society any return to a passive investor of more than 6 to 7 percent could be considered socially responsible.

We might take a clue here from that branch of socially responsible investment that deals with community investments where expected returns are so modest relative to returns on more conventional investments they often feel rather more like charitable contributions. In fact these returns are much closer to the returns one should expect from passive investments in a just and sustainable economy in which the people who actually produce the goods and services that sustain us are properly rewarded, all costs are internalized by the seller and included in the selling price, and we all pay our rightful share of the costs of taxes to maintain the commons.

We might ask: What is the role of the socially responsible investment community in opening a public debate as to what is a reasonable return on passive investment? Are we prepared to come out and make the case that there are in fact some things more important than shareholder return? Are we prepared to point out that we are living under the rule of a financial system that rewards those who disregard the social and environmental costs of their actions with returns of 30 to 50 percent while expecting people of conscience to settle for 3 to 6 percent–and that to accept such a system as a society is insanely self-destructive?

Are we ready to engage a public dialogue from within the investment community on how the system might be redesigned to consistently and reliably reward good behavior and punish bad? One place to start getting the issues on the table would be through effective use of the community’s aggregate voting power.

Robert Monks calls for share holder resolutions holding corporate executives accountable to shareholders for: 1) obeying the law; 2) fully disclosing in their financial reporting what they know or strongly suspect regarding the costs imposed by their firms on the function of society; and 3) minimizing their involvement in political processes. Now this would be a good start.

A recent Business Week editorial advised corporations that want to restore their credibility with the public to “Get out of politics.” This doesn’t just mean ending political contributions. It means firing the lobbyists and getting out of the countless industry associations such as the Climate Change Coalition that are in the business of obscuring critical public issues and blocking public action on essential social and environmental priorities. Let’s face the truth. It mocks the very concept of social responsibility to include in socially screened portfolios corporations that are aggressively using shareholder money to defeat public efforts to raise social and environmental standards through say bottle recycling bills or increased fuel efficiency standards.

Then there is the question of management incentives. Stock options for top management have become so outrageous they are even a rip off of those shareholders who have no concern other than their own return. How about a campaign to eliminate stock options or to find innovative ways to restructure them so they provide incentives for good social and environmental performance?

These would be good first steps. If we really get serious about economic redesign we need to get clear on the difference between a market economy and a capitalist economy, because a market economy is quite a good idea. A capitalist economy is a very bad idea. The capitalist economy is about concentrating wealth and power. A market economy is about people creating their means of livelihood.

Consider what market theory tells us about some of the characteristics of an efficient market economy.

- First it must be regulated to maintain the conditions of market efficiency.

- Individual firms must be relatively small and they must be locally owned by people who have more than a purely financial interest in the firm.

- There must be no subsidies or other externalized costs. They must respond to market demand, not create it artificially.

- There must be no trade secrets that confer a form of monopoly power and trade among communities and nations must be balanced.

So let’s compare these principles with what global corporations are constantly working to achieve.

- First they spend millions promoting market deregulation.

- They strive to reduce competitive discipline by gaining ever greater monopoly power through internal growth, mergers and acquisitions, and through strategic alliances and illegal cartels.

- They institutionalize the most perverse form of footloose absentee ownership.

- They are constantly looking for ways to pass their costs onto the public, including through demands for special subsidies and tax breaks.

- They may spend more on marketing to shape consumer tastes than they actually spend to produce their products.

- They seek to create intellectual monopolies through patents and copyrights.

- They press to free trade from any restrictions that might maintain balance or confine capital within national borders.

- This suggests that capitalism is in fact the mortal enemy of the market as its dominant institutions work tirelessly to defeat the conditions on which market efficiency depends.

It is also worth noting that the marvel of markets are their capacity to self-organize. The institutions of capitalism are, by contrast, models of central planning. Consider the implication of the fact that of the 100 largest economies in the world, 51 are economies internal to corporations. The economy internal to a corporation does not function by market principles. It is centrally planned. The corporate CEO has a power to hire and fire workers, open and close planets, buy and sell businesses, and set transfer prices that would have made any Soviet central planner green with envy, and all without any recourse by the people or communities affected.

Say we set about to restructure the systems and institutions of business along market lines in ways that actually direct the rewards to those who best serve society’s real needs. An essential first step will be to restore a semblance of democracy through serious campaign finance reform so corporations stop writing the rules to their own narrow benefit. This means full public funding for public elections and free use of the public air waves for serious political dialogue and debate.

With political reform in place we can move ahead with a serious anti-trust program to limit the size of corporations and thereby reduce their power to extract monopoly profits and externalize costs onto society. This might start with prohibiting any merger or acquisition unless a compelling public need can be demonstrated. Perhaps it is time for some socially responsible shareholder resolutions aimed at blocking mergers that reduce market competition and concentrate corporate power. We will need enforceable rules that penalize corporations that attempt to pass their costs on to the public. And we will need to eliminate corporate personhood and any special liability protections.

If we want corporations to be responsible to their non-financial stakeholders, then we must align incentives and ownership according. This means turning stakeholders into real owners. I believe private property is such a good idea that everyone should have some and it should include an ownership stake the assets or enterprise on which their livelihood depends. That means putting ownership in the hands of workers, customers, community members, and suppliers–real people who have an immediate social and environmental stake in the enterprise–in addition to their financial stake. A starting point might be to pressure corporate management to restructure Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) to give participants full voting rights to the shares they own. This could be an agenda item for socially responsible investors.

And if you are really serious about this agenda consider supporting Ralph Nader’s presidential campaign as he has a total commitment to the transformative agenda. Neither Bush nor Gore even acknowledges the issues we are discussing here.

These are not small reforms, but neither do we face small problems. Just as the current disaster is an outcome of human choices, it is within our collective means to make different choices–to create a world that works for all–including future generations for thousands of years to come. It is the most exciting opportunity–the most compelling creative challenge–in all of human history. We have the knowledge, the technology, and the necessity to rethink and recreate humanity’s economic, political, and cultural institutions to realize a long standing human dream of peace, justice, and prosperity for all. We must be clear, however, that tinkering at the margins of a badly broken system just won’t do. That’s part of what makes the present human challenge so exciting.