July 1, 2024 (June/July newsletter)

Dear Friends,

During my lifetime (just a blink of an eye in human history), we’ve experienced an extraordinary period of accelerated learning. The transformational advances in communication, understanding, and imagination during this brief period affirm that humans are a species with truly distinctive learning capacities. We are now called to actualize those capacities on behalf of one another, Earth, and creation’s continued unfolding.

We face the paradox that our abuse of these advances has led us to the brink of human self-extinction. What is less evident is the extent to which this period places us on the threshold of a breakthrough pathway to an Ecological Civilization of universal peace, material sufficiency, and spiritual abundance for all.

In my February 2024 newsletter, I made passing mention of this dramatic period of human learning. Every day since, I have found myself asking: Why have we as a species taken so little note of the potential these rapid advances provide? I have no answer to that question. What is clear is that it is essential that we now acknowledge and embrace that potential.

— David Korten

_______

Time of the Great Learning

David Korten | July 1, 2024

Our distinctive human ability to learn gives us a corresponding capacity to shape the future of life on Earth. That ability has demonstrated itself in extraordinary ways during the past 90 years. During this brief and distinctive period of accelerated learning, our species has fundamentally transformed our understanding of creation, Earth, and life. Building on a melding of traditional wisdom and findings at the leading edge of science, we are now positioned to achieve an essential transformation of our human relationships with one another and Earth.

We have abused the products of this learning in ways so detrimental to ourselves and Earth that we now find ourselves on the brink of self-extinction. Simultaneously, however, the advances we have achieved give us previously unimaginable potential to transform our ways of relating to one another and Earth to achieve a future wondrously beneficial to ourselves and all of life.

This brief period of rapid learning includes what some call The Great Acceleration, a name given to the period since 1950 during which humans have caused more harm to Earth than in the whole of human experience tracing back to when the first modern humans appeared on Earth some 200,000 to 300,000 years ago. For some perspective on how far we have come in the last several decades, it’s helpful to look at some of the modern advances we now take for granted.

My lifetime has given me witness to many of the defining dimensions of this transformational period. I was born in 1937 in Longview, Washington, a small industrial town in the northwest United States. It was near the end of the Great Depression from which we learned how to end and prevent serious economic depressions. It was shortly before the start of WWII, from which we learned to turn Germany, Italy, and Japan from deadly enemies to dedicated peaceful allies.

My dad inherited a small local business from his parents and built it into a significant local music and appliance retailer with national visibility and reputation. He took special pride in his commitment to providing expert technical repair services for everything he sold. As the eldest son, the family assumed that I would one day inherit and manage the business. My preparation included assisting with deliveries, installation, and repairs of the electronics, appliances, and musical instruments of that period. This provided a unique opportunity to learn about many evolving technologies of that time.

I recall the excitement when television broadcasting capability was first introduced into our town in the early 1950s. When our store received its first delivery of television sets, they had bulky cathode ray tube viewing screens with snowy black and white images and required roof top antennas—which for a time I assisted in installing. Now viewed as primitive museum pieces, they were an extraordinary technological breakthrough at the time.

My life took a dramatic turn during my senior year in college when I decided not to return home to one day manage the family store. Instead, I committed my life to the work of ending global poverty by helping to bring the secrets of U.S. business success to the world’s poor countries.

My travel to Asia and Africa in the 1960s brought me into my first contact with peoples who had little or no prior contact with the world beyond their isolated local community. Cut off from modernity with no access to electricity, modern medical care, or sanitary facilities, they were still living much as their ancestors had lived for thousands of years.

Few such communities still exist. We are now interconnected as a single global people with capabilities unimaginable only 20 to 30 years ago. We now become accustomed to new technologies so quickly that we tend to forget how far and fast we have come as a species in a mere flash of evolutionary time.

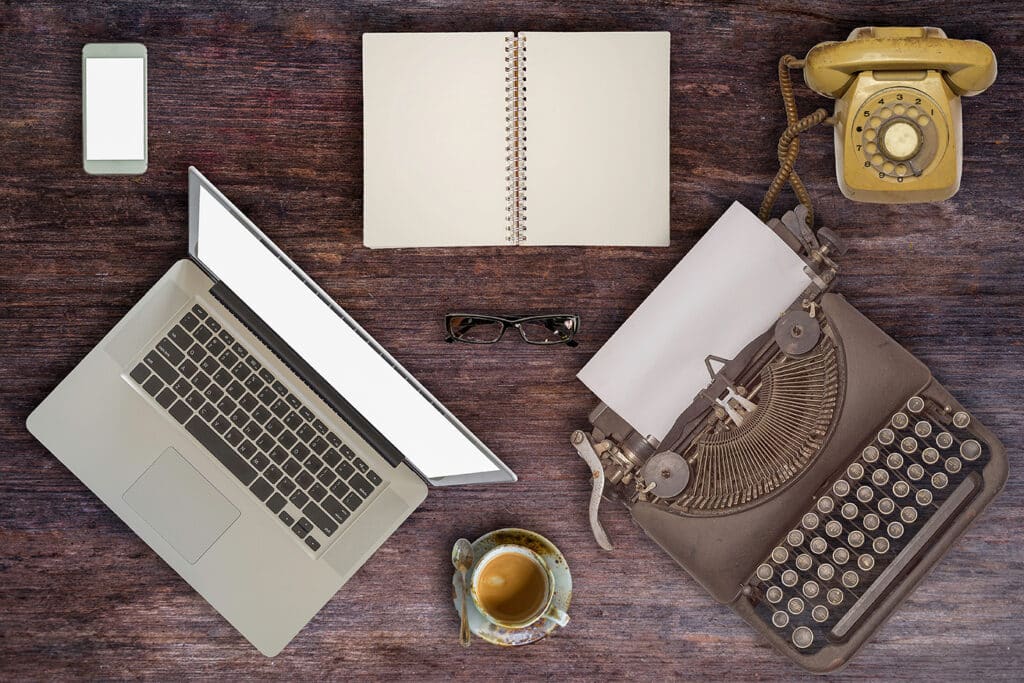

Here is one example. In high school I learned to type on a mechanical typewriter. Electric typewriters were not yet readily available. Nor were copy machines. If I needed a copy, I used carbon paper or produced a mimeograph stencil on my typewriter. If I later needed an extra copy, unless I had initially created and stored a mimeograph stencil, I had to retype it. If I wanted to share the written piece with a friend, my only option was to put it in an envelope with a postage stamp for hand delivery by the postal service.

When I lived in Ethiopia in the mid-1960s, airmail letters to the United States generally took two weeks to deliver. Remote villages that had virtually no contact with the outside world when my wife Fran and I visited them in 1960s in our 4-wheel drive Land Rover, now have internet cafes.

Dealing with numbers had a similar limitation. In the 1950s I had a mechanical adding machine, the most advanced numbers processing technology then available. By the time I was doing the research for my PhD at the Stanford Business School in 1966, Stanford had a state-of-the-art punch card computer that was available for use by professors and graduate students. To process my survey research data, I had to get special training and then spend days preparing a box of punch cards to be left overnight with the computer staff to load and process in a computer that filled a large room.

That computer had a tiny fraction of the capacity of the computer built into the smart phone that now fits into my shirt pocket. This device gives me instant access to a vast pool of human knowledge and information and the ability to engage in direct conversation with anyone in the world, thousands at a time, across previously daunting barriers of distance, culture, and language. It also produces and shares instant photos and videos—capabilities unimaginable just a few decades ago.

Anything I post on my website is now instantly available to nearly anyone in the world. I can type my desired text, or simply dictate it into my phone. Anyone who accesses that information on the internet has the option of getting instant automatic translation into any major world language.

I now have the option of turning to Artificial Intelligence (AI) to instantly draft an essay drawing on a vast global store of knowledge in response to whatever question I ask of it. Yes, the potential for abuse by those who control the programming of AI applications is terrifying. The ethics of the program are determined by programmers who work for corporations dedicated to maximizing profits for their richest owners. The potential benefits to improving our lives and healing the planet are breathtaking. But only if the programmers get the values right.

Other impressive advances in human learning during this same period include improvements in health care and food security that have increased global life expectancy from 46.5 years in 1950 to 71.0 years in 2021. Without them I surely would have died years ago.

In the year of my birth, commercial air travel was in its infancy. The twin propeller driven DC-3 introduced in 1936 was metal rather than wood, could carry 21 passengers and had a range of 1,500 miles. Now the Airbus A380 can carry 853 passengers and the Boeing 777-299LR has a range of 10,800 miles. We send humans to Earth’s moon and peer back into time to view the birth of the cosmos while exploring the depths of the ocean and the inner micro-worlds of physical matter and living cells. One of my granddaughters just finished her doctoral dissertation based on breakthrough telescopic research of black holes.

From both evolutionary and historical perspectives, the advances in our human capabilities during my generation’s lifetime are stunning. We best leave the question of “Why now?” to historians. We need to keep our focus on the more practical question “How can we best use the learning now available to us to advance the transition to an Ecological Civilization?”

We have never previously had the ability even to pose the question as a collective challenge. Now it has become our collective imperative. Paradoxically, our learning during this extraordinary period has drawn us to a recognition of the importance of the wisdom of our ancient ancestors expressed in the ancient African principle of ubuntu, which translates “I am because you are.” Therefore, “my wellbeing depends on your wellbeing.” This nearly forgotten principle of life is currently being reaffirmed and elaborated by contemporary science.

Our human wellbeing, indeed, our existence, depends on the many ways in which life self-organizes to continuously terraform Earth to create and maintain the conditions of air, climate, water, and soil essential to the existence of complex life forms. In a very large sense, all living beings depend on one another.

For humans, learning to use the advances we have achieved over the last 90 years to live in mutually beneficial relationships with one another and Earth is the defining challenge of our time. To embrace this challenge we must come together in common cause as a now interconnected global species to end, repair, and move beyond the damage we have done. We are now positioned to learn to end violence, care for one another with compassion and empathy, and care for Earth while achieving material sufficiency and spiritual abundance for all.

_______

From the Book Shelf…

“Within little more than the life span of my generation, an explosive growth in human propulation and consumption has combined with breathtaking advances in human knowledge and technology to change the world almost beyond recognition. We look inward to observe the behavior of subatomic particles and the inner processes of individual iving cells. We peer far into space to discern the workings of the universe and the dynamic processes of its unfolding. We look back on our own big history to describe in ever more magnificent detail the dynamic processes underlying the evolution of life on Earth.

“Within little more than the life span of my generation, an explosive growth in human propulation and consumption has combined with breathtaking advances in human knowledge and technology to change the world almost beyond recognition. We look inward to observe the behavior of subatomic particles and the inner processes of individual iving cells. We peer far into space to discern the workings of the universe and the dynamic processes of its unfolding. We look back on our own big history to describe in ever more magnificent detail the dynamic processes underlying the evolution of life on Earth.

With this extraordinary perspective, we can see Earth as a wondrous, resilient, adaptive living being to which we must adapt – or die.”

(Chapter 4 – “A Living Universe” – Page 59)

_______

For more Newsletter Essays, visit HERE… If this newsletter was forwarded to you, please sign up HERE to receive your own copy.